HOW CHAMPIONS DO IT

Researched, produced, and prepared by Brent S. Rushall,

Ph.D., R.Psy.

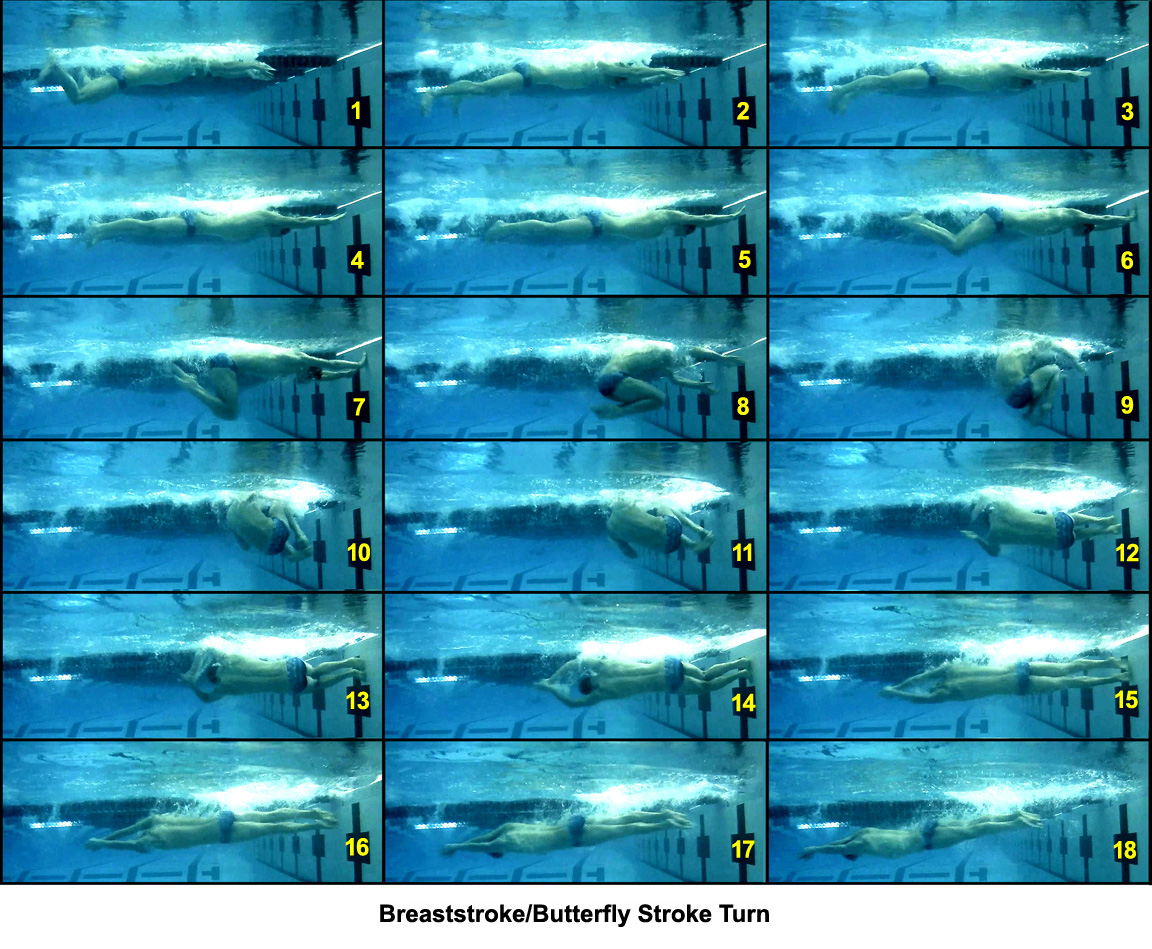

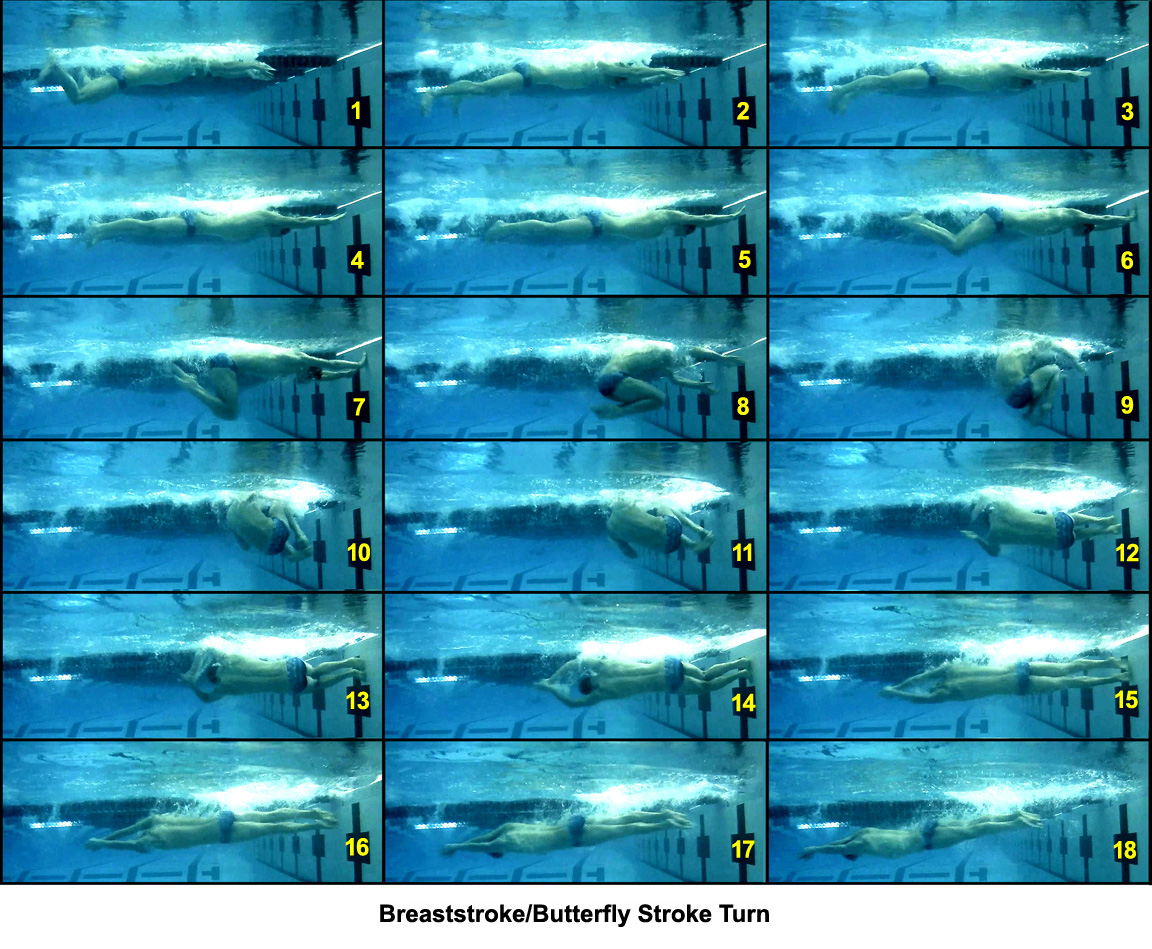

BREASTSTROKE/BUTTERFLY STROKE TURN: THE SHORT-RADIUS TURN

The turn described in this article is appropriate for both breaststroke and butterfly racing. The athlete shown is Michael Andrew, arguably the greatest age-group swimmer in US swimming history. The name Short-radius Turn" was prescribed by Coach Roy Chaney of Colorado.

This turn was developed because of the need to improve Michael's turns in the two symmetrical stroke forms. Although there are some descriptions of symmetrical-stroke turns in the popular literature, there is no consensus as to how best they should be done. This turn was designed from scratch. Several features had to be incorporated to make it the fastest turn possible.

- The turn should be simple and require the fewest movements possible.

- It should minimize vertical movement components.

- It should be completed away from the wall so that the distance covered in a race is shortened as much as possible.

- The principles of biomechanics should be employed where they are appropriate.

This stroke analysis includes a moving sequence in real time, a moving sequence where each frame is displayed for .5 of a second, and still frames.

The following image sequence is in real time. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

The following image sequence shows each frame for half a second. It will play through 10 times and then stop. To repeat the sequence, click the browser's "refresh" or "reload" button.

At the end of the following narrative, each frame is illustrated in detail in a sequential collage.

Notable Features

- Frames #1 through #4: The wall is approached. When a commitment is made to touch the wall, the swimmer should be as streamlined as possible. That is needed so that at any stage of non-propulsion between the finish of the last stroke and the wall-touch, as little resistance as possible is incurred. Michael Andrew streamlines very well in this sequence. The position of the head and the overall horizontal posture are noteworthy.

- Frame #5: The symmetrical both-hands wall-touch is made. The wrists absorb the contact forces. The intention is to keep the arms straight so that any unnecessary distance to the wall is not covered.

- Frame #6: At the moment of touch, the legs start to bend as the initial stage of assuming a tuck position. The head and torso maintain the horizontal position that was achieved in the streamlined approach to the wall.

- Frame #7: The development of a tightly tucked position continues. The tightness of the knee flexion is very desirable. The head and torso still remain underwater and streamlined. The swimmer has bent his elbows slightly being preparatory movements for pushing off the wall.

- Frame #8: Several movement elements happen at once in this frame. The tuck continues with the thighs approaching the swimmer's chest. The aim of the tuck is to be as tight as possible so that when rotation occurs it will have the shortest radius possible, which should result in the fastest rotation of the swimmer. Rotation begins from two actions. The arms push off the wall by extending the slightly flexed elbows and the wrists. As the push occurs, the head is thrown directly backward and the face turned to the side (the shoulders will rotate too). Two forms of rotation are sought. The first is along an axis through the vertical plane that produces spin. The second is a quarter-rotation in the transverse plane that turns the swimmer onto the side.

- Frame #9: The turn has occurred at a comfortable distance from the wall so that the rotating swimmer can bring his legs up well away from the wall. If the body were to be positioned closer to the wall, the explosiveness of the leg drive would be hampered. In this frame the left arm leads the sideways turn and stays low in the water. The right arm should be kept underwater and manipulated forward. It should not be swept in a high arc above the water because that would produce a vertical force that would depress the swimmer deeper into the water, which in turn would compromise the drive of the legs off the wall. The head should be thrust back toward the other end of the pool and not raised. It is likely that no breath will be taken. This no-breathe turn is one of the innovations in this activity. It requires the last breath approaching the wall to be slightly bigger than normal so that an underwater turn can be achieved.

- Frame #10: the two forms of rotation are achieved while the swimmer is in a tightly tucked position. The rotations demonstrated here need to finish when the legs are positioned for a direct explosive plant on the wall. This frame demonstrates that on this occasion, Michael Andrew did not breathe.

- Frame #11: As the rotations continue preparations to stop them have to be made. It is clear the swimmer is well away from the wall and has maintained a fairly consistent depth position relative to the surface of the pool. The tucked position begins to be opened and the arms are moved forward underwater. That results in a lengthening of the axes of rotation so that both forms of rotation slow. As the slowing occurs, the swimmer begins to prepare the leg extensions as the first part of an explosive leg drive.

- Frame #12: Both hands are at head level and are being extended forward to an eventual streamlined position. The body is almost horizontal and still has a little further to drop. The torso is extending preparatory to being streamlined when the leg-drive off the wall is achieved. The legs begin to be thrust at the wall so that they will put the extensor muscles of the legs very quickly on stretch when wall contact is made. The velocity with which the extensor muscles are put on stretch will directly affect the degree of muscle contraction velocity to hopefully generate an explosive drive off the wall.

- Frame #13: The swimmer's legs have contacted the wall. The Achilles' tendons in particular are being put on stretch to enhance the explosiveness of the resulting drive. Lateral rotation continues with the knees pointing slightly toward the pool bottom. The other form of rotation has ceased.

- Frame #14: The drive off the wall has started. The speed with which the arms are thrust forward influences the speed of the leg drive and vice versa. The aim of the swimmer should be to attain a streamlined position at the correct depth to initiate the double-leg kick as the start of the break-out sequence.

- Frame #15: Michael Andrew has done very well by keeping his head down between his arms as much as possible during the whole turn. The drive exhibited here is full and uses all leg joints capable of extension movements.

- Frames #16 through #18. The drive off the wall is followed by a full streamlined posture of the total swimmer. Before the double-leg kick is taken, the swimmer is on his front which satisfies the rules of swimming out of breaststroke and butterfly turns.

Michael Andrew provides a very good model of this simple new turn for breaststroke and butterfly stroke. His turn has achieved that for which it was designed. It is simple, there are no extraneous movements, all the actions occur underwater and in tight deliberate fashion. The precision of the swimmer's streamline in and out of the turn is a marvelous model for emulation.

At practices, Michael Andrew's times for using this turn when compared to his old turn are markedly shorter. The turn achieves that for which it was designed.

Return to Table of Contents for this section.

![]()

![]()